Statisticians and risk managers are pretty good at measuring things so long as they have underlying data. One of the things synonymous with financial markets is numbers – prices, positions, turnover, profits, volumes et cetera. Clever people can take this data and turn into all sorts of useful (and often not so useful) metrics to prove just about any point they want to. Why? Usually to sell something (a financial product) or to justify a position taken, or to argue why a certain a trade ought to be taken. Statistical concepts such as standard deviation, volatility, kurtosis, skewness etc. are calculated daily in an attempt to measure what has happened in the past in order to gain an insight into the future. Alpha and beta are used to garner insight into fund performance in order to select which manager has an edge over other managers (or the markets), or perhaps to argue why active is better than passive management (the constant debate over the efficacy of ETFs as an example).

And numbers matter just as much in the world of risk management. Analysing and crunching data is useful to establish the size of positions and their effect on the portfolio, or a bank’s capital position, should something unexpected or untoward occur (stress testing and scenario analysis). Risk comes in many forms – some is measurable such as the effect on X if Y happens (e.g. what happens to a portfolio should the market drop 20%). However many risks are to a large extent unmeasurable. Reputational risk, for example, is a very difficult concept to measure – the damage inflicted on the Volkswagen brand post their emission’s “issue” is next to impossible to quantify accurately.

One form of risk that is surfacing more and more recently is political risk. In fact I heard a new description of this risk recently on twitter – the concept of political volatility. Investment managers have always classed political risk as a general macro-economic factor that needed to be considered as part of an overall risk management framework. Anecdotally, however, it seems that every day this risk is rising. Again it is near impossible to measure accurately but one thing you can be sure of Brexit, the European refugee crisis, Syria, Donald Trump, the US election, Putin, Ukraine amongst a host of others are most certainly negatively affecting market sentiment. All these things, individually or collectively, create political uncertainty and one thing we know for sure – financial markets hate uncertainty. Markets often fall in the run up to perceived bad news and then more likely than not, when the bad news is finally announced, they rally as the news has already been priced in.

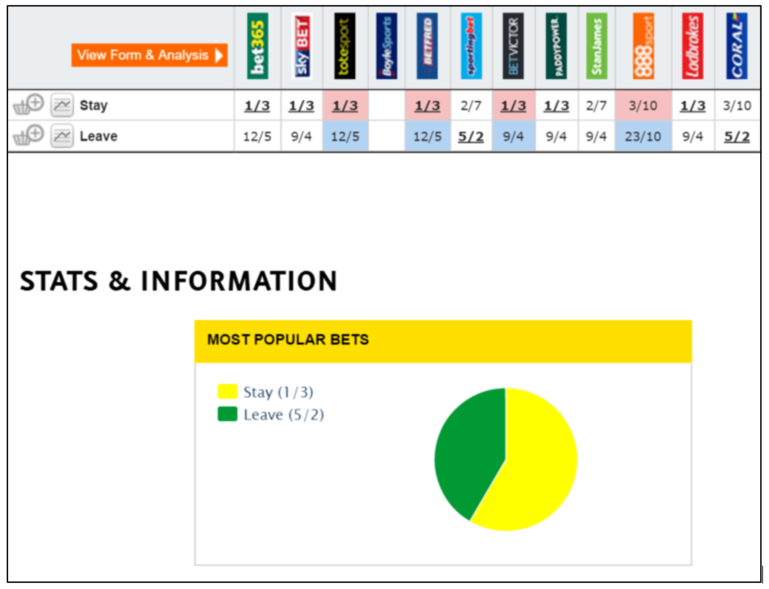

The question is, can political volatility be measured? Betting markets can give an indication as to what people placing real money think for certain events – Brexit (see table below), or US elections. But that doesn’t really accurately measure the general level of anxiety or uncertainty attached to what is happening in the political world. Can these events be hedged? Well yes and no. You can take a view that, for example, that sterling will fall in the event of Brexit and can use derivatives to hedge the risk of losses should this happen. But sterling could rise and you could lose money (on a forward or futures contract, or lose your premium on an option).

So if it isn’t really possible to accurately assign probabilities to political volatility or to hedge the risk away comprehensively what is the fund manager to do? Perhaps we just have to live with this and respond to events as they happen. But if they happen regularly the market will demand a premium for extra risk – as has been the case for emerging markets historically. The bottom line is that these risks are inherent in financial markets. Moreover political volatility is becoming a much more frequent and pronounced risk so we, the industry, need to start to develop metrics to measure it.

Get in touch

Please contact us if you would like to learn more about our solutions