Value at Risk (VaR) models are now thoroughly embedded in European risk management practice and have even received regulatory imprimatur in UCITS legislation. However all models are only as good as the assumptions used in their construction and so, after a month where there were some extreme market moves, it is reasonable to ask how well did VaR models perform?

To recap very simply, a VaR model produces a one day forecast of a loss in an underlying instrument (portfolio) with a stated probability. This forecast is based on the historical performance of the instrument (portfolio). Contrary to what is stated in some documents (CESR/10-788 for example), the VaR forecast is the minimum loss associated with the stated probability. Thus a 99% VaR of €1mm implies that in 1% of outcomes, the portfolio will lose at least €1mm. VaR makes no forecast of the actual loss, just the minimum loss associated with that probability.

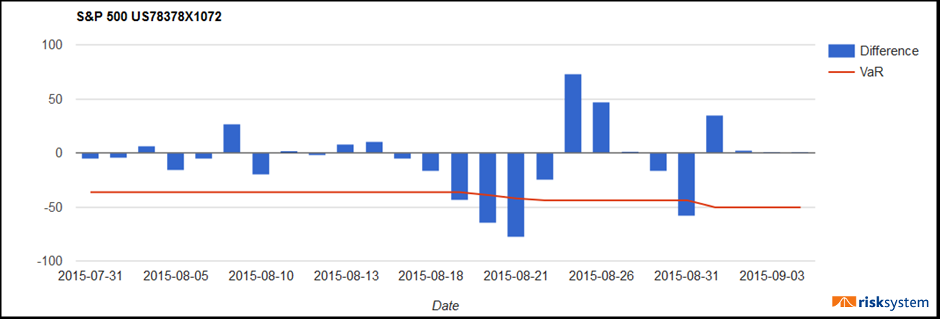

Figure 1 shows the daily change in the value of the S&P index versus the previous days VaR forecast calculated using the previous 250 day time series.

Figure 1: Realised price change vs VaR forecast for the S&P 500

As can be seen, coming into August the VaR forecast for the daily price change was a loss of at least 36pts. This level was exceeded three times in a row on the 19th, 20th and 21st of August. Whilst the VaR forecast did increase as the extreme events happened, on the 21st, the VaR forecast was for a loss of at least 42pts at 1% probability, in the event the realised loss was 78pts, a factor of 1.86 greater than the forecast. By month end the VaR forecast had increased from 36pts to 50pts, an increase of 39%.

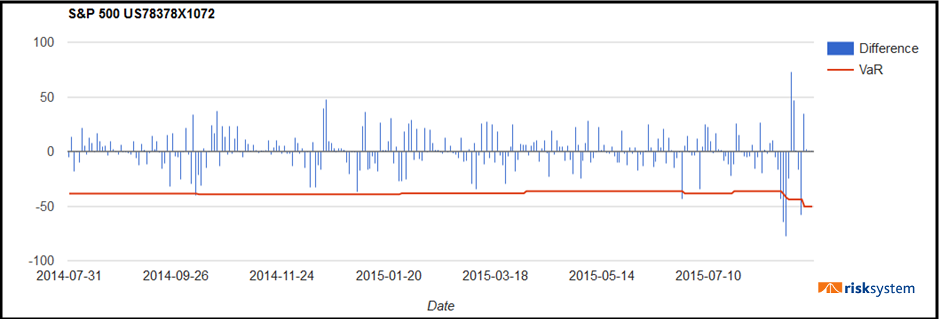

So how did the VaR forecast perform? If you were expecting it to forecast actual losses, very poorly. However VaR never forecasts absolute losses, so in this case the expectation is the problem rather than the forecast. However four days in one month in which the realised loss exceeded the VaR forecast should be a matter of concern given that it would be expected to happen in only 2.5 days in 250. As such it is worthwhile looking at the data that was used to produce the forecast, that is, the previous 12 months history of the S&P 500, figure 2.

Figure 2: Realised price change vs VaR forecast for the S&P 500 for 12 months

As can be seen, the five days of consecutive losses that occurred in August 2015 do not look like any other period of losses in the reference time history of the S&P. One of the assumptions of a VaR forecast is that the past is a reasonable indicator of the future, and clearly the extreme events in August were not well predicted by those of the previous twelve months.

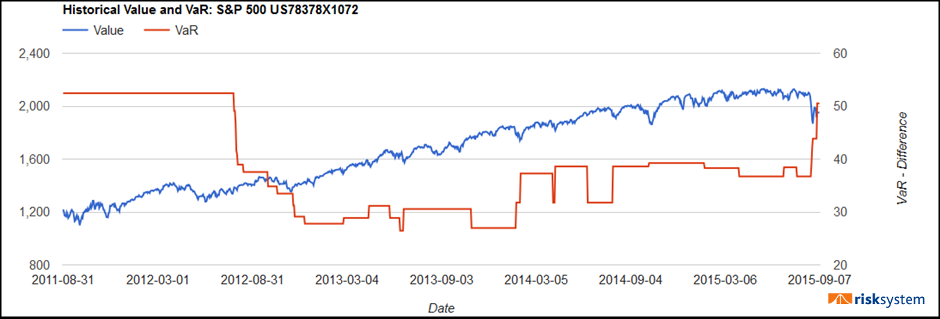

Clearly one issue is in the time series that is used to estimate the forecast. Following a year in which markets have been relatively quiescent, the VaR forecast of minimum losses may well be deficient. This has been recognised by bodies such as the European Banking Authority, which advocates the use of “Stressed VaR” as well as straight historical VaR. Stressed VaR estimates a minimum loss forecast using periods of historical stress as the reference time series. As can be seen in figure 3, where data from the July 2011 Eurozone crisis was included in the time series, the stressed VaR (absolute value) was more appropriate to the events of August than the previous 12 months.

Figure 3: Long term value and VaR of the S&P 500 index

In conclusion, a VaR forecast is as good as the assumptions that underlie it. Whilst some fund managers may complain that they are now hitting risk limits because they were leveraging up in a period of relative calm, using a variety of risk metrics such as VaR and Stressed VaR ensures that such actions would not have been taken in the first place. In other words “it is not different this time…”